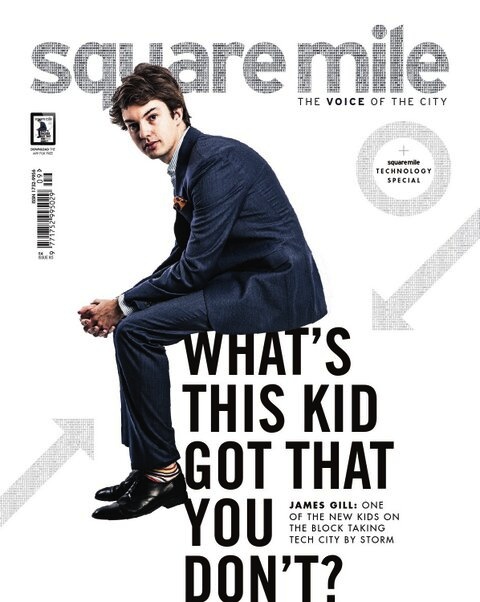

Cover story for Square Mile Magazine, December 2013. Original article here (p75-79).

Generation Tech:

Generation Tech:

Interview with James Gill, co-founder and CEO of GoSquared

Prufrock Coffee is buzzing even though the lunch rush has come and gone, as James Gill isn’t the only startup CEO who likes hauling up in the airy Clerkenwell cafe to talk shop. While we wait for our caffeine, new business ideas are being doodled on napkins all around us, and Gill declares proudly that GoSquared has just had its best month yet. In jeans and boating shoes, his graphic print t-shirt seem fitting for a 22-year-old CEO, but Gill has actually had plenty of time to get his bearings – GoSquared, the real-time web analytics company, was founded by Gill and two friends when they were just 15 years old.

“I have definitely had my 10,000 hours doing design,” says Gill, peering up on the wall to the sign that reads ‘10,000 hours’, a reference to the idea that mastery only comes after having spent that long practicing. “That’s what started us on the route to GoSquared. If you go back to the beginning I would spend ages drawing things, and that evolved into drawing interfaces and designing websites.” When he was 14, Gill inherited an old Mac from his father’s office, and started playing around with Photoshop. “I picked up this magazine which was a basic intro to Photoshop, Flash and all the tools you needed to build a website at the time. I would spend all my time outside of school learning how to design things. When I met Geoff [Wagstaff] and JT [James Taylor] they were much in the same way, but on the programming side.” As the trio started making websites they learned as they went along, first designing features and then working out how to get them to do what they wanted. “Before we started GoSquared we knew almost nothing, so it was all about spending hours and hours working things out. It’s definitely taken more than 10,000 hours.”

GoSquared originally started out selling advertising squares (hence the name), with analytics being a sideline that quickly became the main offering. Unlike the main competitors, GoSquared delivers web analytics in real time, enabling companies to respond immediately to problems or opportunities. While CEO Gill’s job has long-since developed past the original remit, good design remains at the heart of the GoSquared philosophy: “Designing the product isn’t just about making it look pretty. It’s about which features really matter, getting rid of the things that don’t, and making sure we design something that not just looks great but also works great.”

Competing with the “hellishly complex” Google Analytics, and Adobe Omniture, Gill credits better design as a key reason GoSquared has been able to gain a foothold in the analytics space. Being young and nimble helps too: “By having a relatively tiny team who know what they want to do, we can be much more unified in everything we make. … Maybe a time will come when we have to expand, but right now we love it because we don’t need to have too much structure or too much process. People get to stay more autonomous.”

A lot has changed for Gill and GoSquared over the past two years, though. While they started the company while still in school, the trio was well on their way to university when Passion Capital co-founder Eileen Burbidge came after them with an offer of funding. Gill dropped out of university after five weeks to give the company a proper go.

“It was very much about the three of them as a co-founding team, says Burbidge when asked why she pursued GoSquared. “Given their age, and the fact that their business had already been trading for five years at that point, it was obvious they were ambitious, proactive and able to secure clients and generate revenue.” Their instinct for design and user experience was “extremely impressive”, says Burbidge, and integral to how they approach software development.

GoSquared has since raised more money from Passion Capital and Atlas Ventures, but Gill admits it’s been a challenge: “Everyone dreams of having their investment in the bank, but once you do, you have the pressure to grow much faster than you were previously. Not just with the users you sign up and the revenues you make, but also in terms of building the right team. We were really caught off guard as to how difficult it would be to build a team: to find the right people, to bring them up to speed, to get them working to your vision and to keep them happy and excited every day. We are still learning how to do that.” This CEO gig is, after all, Gill’s first job, unless you count some work experience at Oxfam: “Yes, I’ve never even had a boss!”

“It still amazes me that we have thousands of people using these tools we have been building. That is an amazing feeling.” Gill pauses. “I used to think, do I want to be an artist or do I want to be a designer? With art, people look at what you create and admire it, but with design they rely on it to get their jobs done. … I still love coming home and saying that we have created something.”

While analytics has traditionally been a somewhat dry topic for back-office staff, Gill believes this is the sort of information that will be driving businesses in the future. “We are approaching analytics from the point of view that everyone should have this data, and we want to deliver it in the easiest way possible to understand.” Eventually, this will mean providing not just raw data, but fully drawn conclusions for action: “This is a massive challenge and a heck of an opportunity for us. The analytics market is still in its infancy.”

A Londoner at heart, Gill is proud to be building GoSquared in the capital: “The London startup scene is getting more and more exciting, with so much having changed just over the past few years.” Born in Blackheath before his family moved to Kent, he now lives in the city with his girlfriend. While not blind to the allure of Silicon Valley, he has no plans of moving: “Maybe I’m naive, but I still like the idea of building a company in London that can compete with companies over there. We have so many talented people in our team and we have great investors, so I don’t see why we can’t keep growing as a company from London. And to show those Valley guys us Londoners can compete!” While Gill admits the London scene has its share of people who “spend all their time at startup events and don’t really do much else”, there’s also a lot of talent: “There’s a heck of a lot of smart engineers and developers on the scene. The main challenge is probably bringing them together and forming teams that can achieve something.”

With over 30,000 websites now using GoSquared analytics, is Gill scared of failing? He hesitates, but only for a second: “I don’t really think about it. For me there isn’t really an option but to make this work. I’ve sunk seven years of my life into this!“ To be fair, the worst case scenario for GoSquared at this point is probably a buyout, offers for which are frequent, confirms Gill: “But we really don’t want to get bought out!”

While Gill is doing “everything I physically can” to push GoSquared, there’s time for other things too, just about. For most things there’s an app: “I have my Nike+ running app. The YPlan app is great, they’re a London startup that help you find events.” He pulls out his iPhone and shows it to me, along with another couple of apps whose design he admires. Gill is a regular at the rugby to support the Harlequins, and frequently goes back to Kent to see his “amazingly supportive” parents. Before I’ve even asked he tells me about his girlfriend Emma, who has just started working for another London startup. He loves the London food scene, especially places like ‘Dirty Burger’ where they do just the one burger but what a burger it is – a well-designed concept.

But as most people who truly love their job, Gill never really stops working: “I don’t really have that switch between work and home. On the average day I get up, have a shower, get the Tube and then I spend some time alone in a coffee shop before I go into the office. I’m often there until 8pm, but even after that there’s always someone to reply to, something to sort out for tomorrow. There’s always so much going around in your head.” He seems happy though, excited to be in the hotseat, even though as he says, the startup life swings wildly between highs and lows. Is he saving the sports cars and parachute jumps for his mid-life crisis? “Mid-life? Do I have to wait that long?” Gill laughs. “Maybe someday. But for now I get plenty of adrenaline just going to the office.”

***

Roundabout Royalty

Jude Ower, Playmob

Gaming, business and charity comes together at Playmob, the company founded by CEO Jude Ower in 2007. The company, whose technology enables charity elements to be added to existing gaming features, lets charities get a cut from in-game purchases. The games developers benefit too, as the charity link makes players spend more. Working closely with product director Caroline Howes, Ower comes from a background in consultancy and marketing. Now based in Fitzrovia, Playmob has raised more than $1 million to date, from the likes of Nesta, Midven, individual angels and startup accelerator Springboard.

Joshua March, Conversocial

Conversocial helps businesses keep track of customer services issues raised on social media, so they can respond right away to snarky Facebook posts and bitchy Tweets. By efficiently keeping up with the social web in real time, companies can provide great service and better manage their reputations. CEO Joshua March co-founded Conversocial alongside COO Dan Lester in 2009. A year earlier the duo had founded app-development agency iPlatform, which was acquired by Betapond in 2012. Shoreditch-based Conversocial has raised $7 million in funding, and last year opened a New York office.

Julia Fowler, Editd

Frustrated with the lack of provable information to predict trends in the world of fashion, designer Julia Fowler came up with the idea for Editd. The company mines and examines data to help the fashion industry measure trends and the market. Co-founder and CEO Geoff Watts brought the data processing expertise to Editd, and now aims to make the company the definite real-time resource for the industry. Established in 2009, Editd has the support of startup incubator Seedcamp, and later raised $1.6 million in a funding round led by Index Ventures.

Damian Kimmelman, DueDil

DueDil is making waves with its database of information on private companies in the UK and across Europe, letting subscribers access 20 years of financial and corporate information on private companies. CEO Damian Kimmelman founded the company in 2010, having previously founded two companies: a London-based digital agency in 2007, and a Chinese peer-to-peer online gaming platform in 2005. DueDil wants its services to lower the barrier to entry for entrepreneurs and developers, enabling them to integrate data directly into their applications as well as building new services.

Hannah Wong, Foodity

Foodity turns recipes into shopping lists, transferring ingredients for new dishes to online supermarket shopping baskets. Working with major brands and retailers to streamline cooking and shopping, Foodity also makes suggestions to users based on what’s most popular, affordable or best quality. Having raised £450,000 to date, the Waterloo-based company is currently in the process of raising an expected £2.5 million in new funds. Operations lead Hannah Wong is the impetus behind the company, having co-founded Foodity in 2009 in the hope of helping people make better eating decisions. She previously set up meal-planning website ‘The Resourceful Cook’.