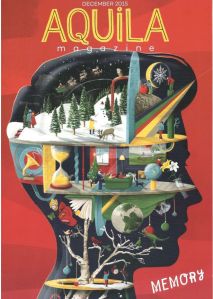

Aquila Magazine for children, December 2015.

The curious link between smell and memory

Why is smell such a strong trigger for bringing back memories? And what happens in our brains when a memory comes flooding back?

Smells have a funny way of bringing back memories you hadn’t thought about in a long time – maybe even things you’d forgot all about. If you’re not sure what we mean, just go and take a whiff from a bottle of sunscreen. It may be winter right now, but it will bring you right back to the beach, or the park, or wherever you were the last time it was hot enough to need to put on suntan lotion. But even if it’s snowing outside, chances are the smell will trigger memories and feelings of summer, and they’ll come flooding into your head, far more intensely than they would by just talking about it.

This little memory trick works with all sorts of scents we have an emotional connection to. Think about how the smell in the air changes when summer turns to autumn, and it can only mean one thing: school’s back. Or if you’re in a car or train on the way to the sea, and you can smell the saltwater long before you can see it. Many of the smells we experience in childhood will act as doorways to memories when we’re grow up, waiting to be rediscovered if we smell something just like it again. Say if your grandfather is a woodworker and you like spending time in his workshop, the smell of wood shavings will probably remind you of this for the rest of your life. Sometimes the special smell can be really subtle, like the smell inside a toy chest or a wall clock, meaning you may not even realise it has meaning to you. But one day in the future you could find yourself smelling it again, and the effect can be striking: suddenly you will be right back to the place, and maybe even the time, where you were the first time you experienced that smell.

But how is it possible for smells to do this?

Out of the five senses – smell, sight, touch, hearing, taste – neuroscientists have discovered that smell is the oldest. What they mean by this is that in the history of evolution, creatures were early to develop the ability to “smell” chemicals in the air and water around them. Because of this, we can say that even bacteria have a sense of smell. But while we’re good at describing how things look or taste, we’re actually pretty bad at describing how something smell. While we describe tastes as sour or sweet, we usually resort to comparing smells to something else – like fresh bread, a meadow, or dog poop. Or as you might say if a smell triggers a memory: “This cake smells like my grandma’s kitchen.”

Let’s take a look at how we process scents inside our brains. The part of the brain responsible for handling smells is called the olfactory bulb: it starts inside the nose before running up into the brain. The olfactory bulb has connections to two other parts of the brain: the amygdala, which deals with emotion, and the hippocampus, which is very important for creating memories. Most other senses don’t touch on these areas as they travel into the brain, meaning they’re not as likely to bring back memories of the same intensity. Maybe that’s why hearing the word “rose” isn’t as effective for remembering as smelling a rose?

Another unique thing about smell is that it moves very quickly to reach deep inside the brain, unlike the other senses which travel along a less direct pathway. Take vision – it starts in the eyes of course, before moving on to a relay station inside the brain called the thalamus, and only then moving further into the brain. Hearing does the same thing. Smell, however, skips the extra step and goes straight for the olfactory bulb. We don’t quite know why this happens, but having a straighter route with fewer pit stops may account for some of the reason that smells can hit us so hard. Researchers have actually discovered that using words to describe things can make the memories less intense, because when we talk about something that’s happened, we start to think of it like a story that we’re shaping, instead of just experiencing raw emotions.

But why can smells bring back memories so faint we thought we’d lost them? We’re not completely sure why this happens, but there’s a few clues in the brain’s memory centre, the hippocampus. Here’s one way to think about it: if a person were to suffer brain damage that affected their hippocampus, they would struggle to remember things after they had happened. But they could still learn new things. So for example, if that person with brain damage were to learn how to ride a bicycle, they wouldn’t remember learning it – but if given a bike, they would be able to ride it. This is because the memory of learning, and the ability to ride a bike, is saved in different places in the brain. That makes it possible to forget the smell of fresh snow at Christmas, but smelling it again years later could still trigger the experience of snow, and we’d feel something. So even if we have lost the memory, the experience could still be kept safe inside our brains, waiting for the right smell to bring it back.