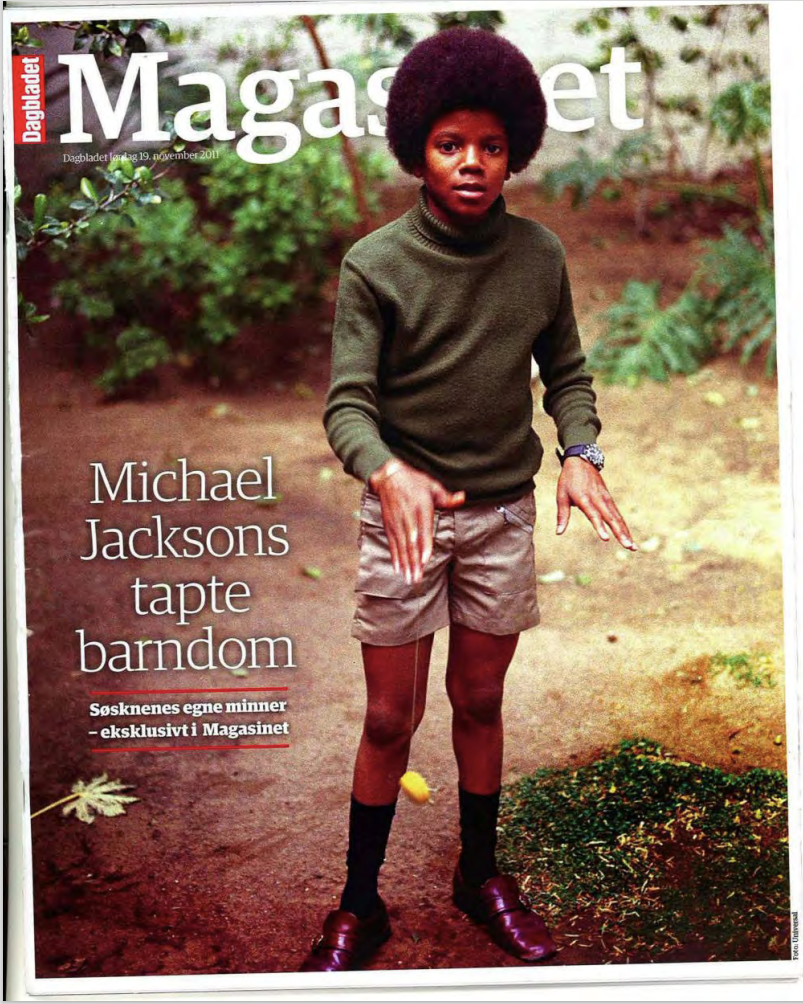

Førstesideoppslag i Dagbladet Magasinet, 19 november 2011.

Jessica Furseth

Published in The Simple Things, January 2025.

Midwinter doesn’t really have many smells of its own. Beyond the invitingly acrid aroma of pine and the icy metallic scent of snow, this season’s smells are mostly memories of things that happened before nature went to sleep. Such as the baked goods spiced with ginger, cardamom and nutmeg, grown in summer and dried for later. Or the earthy whiff of wool jumpers that have become damp, bringing to mind sheep grazing in green fields. And as I grew up in a house with a woodstove, a classic winter scent for me is the sweet smoke of burning logs, with sap crusting around the twig holes as a reminder that inside every tree that’s currently bare, spring is waiting. So many good things of winter are the labour of warmer seasons, and our foresight to put away some of our good fortune so we can enjoy it later.

Except for citrus, that is – this is a delight that belongs solely to winter. Oranges are an unexpected flashy celebration of the coldest months, bursting in the door with unmistakable tang and cheeky brightness. January is peak season for citrus fruits of every persuasion – this is when oranges are at their most juicy and sweet. Or if you like them tart, this is the time for blood oranges, lemons and grapefruits, and let’s not forget the Seville orange, the queen of marmalade.

But for me, the citrus I look forward to the most each winter is the little oranges known as satsumas, clementines or tangerines – technically they’re all varieties of mandarins, but can you really tell the difference? They’re all satsumas to me – orange’s sweet, sparky little sister who’s here to just have fun.

When I was a kid in rural Norway, we couldn’t get satsumas outside of the winter season, making them a rare and longed-for treat. Thrilled at their arrival after what felt like forever, I’d bring them to school with my packed lunches. All my friends did the same – early in the season we’d bring one per day, but once January rolled around and there were fewer sparkling lights to look at, the number was upped to two. That’s the beauty of satsumas – they arrive just in time to claim their place in Christmas stockings, but when all that’s left of yuletide is some rogue tinsel and the dried-up pine needles ground into the carpet, their party has only just started.

Hitting their prime in January, satsumas add a spritz of brightness to a month where you sometimes have to really look to find it. I still remember how genuinely exciting those sweet little satsumas were to us – when we started school in the late 80s we weren’t allowed to bring in sugary treats, and it hadn’t yet occurred to us that rules could be broken. It sounds almost ridiculously wholesome now, but satsumas really were up there with sweets for us, during their brief, glorious moment of lighting up the darkest season.

If something is good, must more be better? Sometimes a kid would show up to school with a whopping three satsumas, but the excitement over this abundance would soon give way to disappointment – the third was always one too many. These days you can get oranges, big or small, all year round, but why? Like bringing three satsumas to school, it seems like a great idea until reality catches up with you and you realise you’ve been greedy. A summer orange makes this brutally clear as it’s often mealy, dry, and tough to peel. The whole thing just feels forced, because it is – it’s a fruit grown out of time. The same experience awaits if you buy a punnet of strawberries in winter: they look red enough, but the first bite reveals its hard unripened insides. You can shine an artificial light on a piece of fruit all you want, but nature knows you’re cheating. As someone who enjoys perusing a full range of nut milks at the supermarket it feels a little hypocritical to say this, but sometimes I wish satsumas were only available when they’re actually in season. It would save me from dry and disappointing mouthfuls, and sharpen the pleasure of enjoying them only when they’re at their best.

Right now, beautifully ripe citrus fruits are arriving in Britain by ship from Southern Europe, mostly from Spain, cradled carefully in cooled containers. I like to buy the satsumas that come in those little wooden boxes, still with a couple dark green leaves attached. My favourite thing to do is to put a satsuma in my pocket whenever I head out to seek out some winter light. I eat my mini orange as I walk, putting the peels back in my pocket – when I find them later they may have dried up, but they still carry a faint whiff of winter freshness.

Lately I’ve been buying a lot of navel oranges too – they’re the ones that look like they have a belly button. They have softer and thinner peels that come away without much resistance, revealing a supremely juicy treat. I like to keep one on my desk all day until the sun starts to set, and as I eat it I’m reminded of a children’s book I saw once, about an orange that’s mistaken for an egg from the sun. As the juice runs down the back of my throat I think that sounds about right – it tastes the way the sun feels.

Published in Extra Crispy, April 2017. Original story / Archived story.

It is, in fact, possible.

On his 30th birthday, Luke Abrams received 30 pounds of Red Robin-brand bacon—”Applewood smoked!”—from a friend who was a cook at the chain. “Red Robin is famous for their bacon. It’s like crack,” Luke explained. “I don’t know what sorcery they perform, but it always comes out perfect. It’s not brittle, so it snaps; it’s not floppy and undercooked; it’s not pale pink but this nice rust color. It’s thick and smoky and ah!” As you can’t buy Red Robin bacon wholesale, the perfect bacon experience was not one Luke could hope to replicate at home—until that fateful birthday.

Is there such a thing as too much bacon? At the time, Luke Abrams didn’t think so. So the Saturday after his birthday, he woke up with a mission to make the perfect bacon, no matter how much consumption that took.

Normally, Luke would cook bacon on an oven tray, but even with the good stuff he still couldn’t replicate the restaurant experience—part of the secret was clearly in the cooking. “My dad told me than when he was growing up, his mom kept a big Folgers coffee can on top of the stove, filled with bacon grease,” Luke explained.

Grandma Eva, who was healthy long into her 80s, would use it for cooking, digging in with a wooden spoon to get a solid dollop. This, said Luke’s dad, was the superior way to cook bacon: a cast iron pan filled with an inch of fat. “The bacon grease acts as a heat transfer medium,” says Luke, who’s an engineer. A frying pan results in uneven cooking, and you avoid this by submerging the meat—not to mention how it means more fat stays within the rasher.

So Luke started cooking bacon while preserving the grease—the first few batches weren’t Grandma Eva bacon, or Red Robin-esque bacon, but, you know, there wasn’t anything wrong with it either, so he ate it.

“By batch seven I had my inch of bacon grease, and I’m like, oh my god. I think I’m onto something. This is the best bacon I’ve ever had.” Luke’s eyes light up at the memory. As he put on the tenth batch he was red and sweating, the kitchen was smoky and the stove was a puddle of grease. But Luke ate the last batch too, taking the total bacon tally to 100 strips.

The next morning, Luke stepped out of bed and immediately fell over. “I couldn’t stand. I put a foot on the floor and this sharp pain rocketed all the way up my right leg. … I was wracking my brain. Did I stub my toe? How can you get injured in your sleep!” Luke hobbled around all day, confused and miserable. The same thing happened Monday morning, when he had to go to work but couldn’t drive. “I realized, I’m going to have to go to the doctor!”

At that point, Luke hadn’t been to the doctor since he broke his collarbone when he was 17. The check-up took place on Tuesday, and the pain went away on Wednesday, 72 hours after it started. Finally, he heard back from the doctor: amazingly, Luke was in the 99th percentile for health. His diagnosis: acute gout.

Too much bacon can certainly cause an attack of gout, says Caroline West Passerrello, a spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. “Bacon is high in purine. The body converts purine to uric acid. If uric acid builds too quickly and can’t be eliminated, it deposits as crystals in the tissues. That’s what cause the intense joint pain, swelling, redness, and possible temporary immobility.”

In the Middle Ages, gout was associated with the nobility, as only the wealthy could afford to eat the rich diet that might cause gout. You’re still more likely to get gout if you’re a man or if you’re overweight. “But gout could happen to anyone,” says West Passerrello. Everyone’s purine tolerance differs, so there’s no way of knowing what amount of bacon is safe for you unless you’re willing to test it out.

Luke still loves bacon, but he’s no longer so cavalier with portion sizes. Because yes, says Luke, there’s definitely such a thing as too much bacon: “I call it the Gout Line. I don’t know where my Gout Line is, and I’m unwilling to do the studies to find it. I’d say that for me, it’s somewhere between 20 and 100 strips of bacon.”

Published in Garage by Vice in March 2019. Original story link / Archived story link.

The permanently closed Lord Napier pub in Hackney is a never-ending piece of community art, but how long can it stay that way?

I first saw the Lord Napier in Hackney Wick ten years ago, walking down White Post Lane when I happened upon this closed-down, derelict East London pub. In the picture my friend Matt took of me I’m standing in front of an orange, yellow and pink splash of graffiti, which is how the building looked that day. But the Lord Napier is a living piece of street art, and chances are it will look different on any given day.

On Google Street View, the default image shows the Lord Napier as of March 2018, covered head to toe in bold color. But if you click on the little clock in the top left corner you’ll find all the previous Street View photos of that spot captured through time, back to 2008 when Street View was launched. A decade later, this technology has become a surprising treasure trove: the time shifting feature lets us open up the history of a place with a simple slide of the finger.

The decorated Lord Napier has become a symbol of Hackney Wick and Fish Island, once an unappealing patch of inner London where artists moved in at the start of the millennium, attracted by warehouses and cheap rent. But the run-up to the 2012 London Olympics changed everything, as the event was held right on the Wick’s doorstep. The Olympics triggered a rapid and aggressive gentrification that continues to price out artists and other locals in this run-down urban area, threatening the very survival of what was once Europe’s densest arts hub.

Cities are constantly evolving, but gentrification has hit East London hard in the past two decades and Hackney Wick could soon be beyond recognition. But in Street View, the city exists in all states at once. The archival pictures of the Lord Napier show a relatively modest level of graffiti at the front of the building in the early years of Street View, spreading out to the side facing Hepscott Road. After 2012 is when things start to get really interesting, as street artists start taking to the Lord Napier as a canvas to display their craft – not just on a corner, but covering the whole damn thing. In 2014, Street View captures the Lord Napier washed in a pastel rain, the work of an artist by the name of HRS. In 2015, it’s covered in three giant black and white faces looking down from the wall as if in horror, painted by street artist Nemos.

The Street View photos of the Lord Napier reveal not just the changing graffiti on the building itself, but also the evolving cityscape around it: the old factory buildings are torn down one by one, replaced with flats that few of the locals can afford to live in. And yet the Lord Napier remains, increasingly as a symbol of what Hackney Wick used to be: a fantastic explosion of mad, noisy creativity built by misfits and underdogs. The Lord Napier, like the WIck, is grotty, insistent, and glorious – the phrase written across the top of the building puts it perfectly: [From] Shithouse to Penthouse.

The most recent Street View picture is a year old, but it’s reasonably similar to what the Lord Napier looks like today. A lot of the art, especially the top section of the building, is from a project that took place in July 2016, the last time the pub received a major artistic overhaul. This was when local artist Aida Wilde curated a 48-hour art takeover, inviting local street artists whose work was known across East London if not also even further afield, including Sweet Toof, Mighty Mo, Mobstr, Dscreet, Malarky, Donk, Static, Teddy Baden, Sony, Xenz, Charice, Stik and Done.

“It was like a last blowout before for the party fizzled out,” Wilde tells me over the phone. “After that, about 70% of the people who’d worked on the pub were gone within the year.” ‘Save Yourselves’ was a true community effort, with local organizations providing paint and equipment: “The experience was so intense!” Wilde laughs. The phrase across the top – Shithouse to Penthouse – was the first thing they did: “That’s Edwin – I think he’d done it a year or so prior on another wall in the area. We started with that because we thought, if anyone stops us before we’re finished, at least that’s done.”

*

The Lord Napier has become a symbol of Hackney Wick – something that the locals who resent the changes can look to for reassurance that some things still remain the same. The first record of the Lord Napier pub is from 1863, and by all accounts it was a standard English pub serving area factory workers. Graffiti appeared not long after the pub closed in 1995, but it’s prime real estate now – how much longer will it stay the same?

When I first discovered that plans were underway to refurbish the pub, I assumed the worst: more unaffordable flats. But that was before I’d met Stewart Schwartz, the owner of the Lord Napier and the man who decides what happens next. “We’re just going to clean it up and refurbish it, to its original style,” Schwartz tells me as we sit down for coffee at the White Post Café. It’s going to become a pub again! “It’s an iconic building, and hopefully it will be a central hub.”

Born in Hackney, Schwartz started a printing business in the Wick in 1984 before expanding into property. He owns several buildings in the area and is landlord to many artist studios, and no, he asserts, he doesn’t want to build any flats. Schwartz bought the Lord Napier about 14 years ago. “At first we didn’t do much with it. There were a few raves in there, and as time went on it got into a worse state,” says Schwartz. His initial plans to extend the building into an artist complex fell apart due to planning issues, and when the Wick became a Conservation Area the pub was listed as a “heritage asset”. So now, Schwartz has decided to restore the 1920s exterior with the two-tone green glazed tiles, and he’ll be adding an upstairs fine dining room as well as a also roof garden.

But what about the street art? “It’s a bit Vivienne Westwood, isn’t it. A bit Malcolm McLaren!” Schwartz laughs. Aida Wilde sought permission in 2016, but most of the time, artists have taken matters into their own hands. “People have come along and done graffiti – they just do it. What can you say? If it becomes a feature, fine. Let’s get on the bandwagon, lets ride with it.”

While Schwartz doesn’t seem too concerned about whether or not the refurbished Lord Napier has a street art element, the heritage statement from ZCD Architects says the graffiti represent “an important part of the pub’s history” and that it should indeed be represented “in some form” in the next iteration of the Lord Napier. In the planning statement, the architects suggest that maybe local graffiti artists could be invited to create custom work on the brickwork of the pub: “We propose to repeat this process annually in order that the facade retain a freshness, as well as allowing the pub to become a ‘living artwork’.”

These are the last days of organic, spontaneous graffiti on the Lord Napier – the building work has just started. For those who see the pub as a symbol of resistance in Hackney Wick, it’s a strange feeling: it won’t be the same, but the next iteration of the Lord Napier will hopefully be a place where the people can gather and admire local street art. Even if it’s a lot cleaner, it’s a nod to what was once here. “People need to know what kind of creative artists lived here,” says Aida Wilde. “I really don’t think anywhere else exists like Hackney Wick.”

Published in Huck Magazine, June 2019. Original article link. / Archived story link.

The curse of the British pub refurbishment

The Disappearing City

It’s the end of an era for Norman’s Coach & Horses on Greek Street in Soho. By the end of June, Fuller’s, the brewery that owns the freehold of this crown jewel of old Soho, will step in to run it as a spruced-up managed estate. To quote Alastair Choat, who took over the Coach from “London’s rudest landlord” Norman Balon 12 years ago: “What the fuck?”

The Coach & Horses is more than a pub – it’s a deeply loved London institution. Nearly 12,000 people have signed the petition to stop Fuller’s from taking over. If you’ve been there, with its blond wood and red light, you’ll understand why: the place is full of people talking and sharing stories over drinks, and while it’s busy there’s somehow always a seat. The Coach has a feeling of community that’s rare to find in central London.

I first met Choat last December, when I was researching a hunch I had about Greek Street being the last great, shit street in Soho. I’d fallen in love with the Coach – the beating heart of Greek Street – years before, one night when I wandered in during one of their piano singalongs. The landlord invited me for a pint, where he told me about the moment that he himself was charmed by the venue, just before he took over the leasehold: “We walked in the double doors on Greek Street, through the pub, and out the doors on Romilly Street. I just went, ‘That’s the pub we want to buy. That’s the one.’” Choat assured me that day he had no plans to change anything at the Coach, which has been there since 1847: “It’s rough around the edges, but I like it as it is.”

I’d asked Choat that question because so many fantastic pubs succumb to the scourge that is “refurbishment”. Last year another Soho landmark, the Pillars of Hercules, was transformed from an old and sticky (but great) pub to a cocktail bar. Sure, there are times when a refurb is needed, and sometimes you need to change the carpets to keep things sanitary. But for a good old boozer, more often than not a refurbishment will rip out the heart of the place.

Fuller’s have said they will be restoring The Coach to its “former glory and retaining all of the features that have made it such a famous pub”. But the glory days of the Coach was Balon telling everyone to fuck off, and one of those fantastic “features” is that Choat (allegedly) lets people smoke inside the Coach on Christmas Eve – it’s one of those weird and wonderful Soho moments you can’t put in a spreadsheet. The appeal of the Coach has little to do with the decor, and everything to do with the spirit that Balon infused into the place over six decades (which Choat has preserved). But soon, the Coach’s sweary smoking days are over.

So what do you do when a Soho institution is dying? As devastating as it’s been, Choat and his daughter Hollie have put up a hell of a fight. And they’ve given their patrons one last Coach & Horses moment that will be talked about for years to come: a special production of “Jeffrey Bernard is unwell”, the West End play chronicling Jeffrey Bernard – writer, alcoholic, 4x divorcee – who once got locked in at the Coach overnight after falling asleep in the bogs.

The pub was packed on press night, with Balon in the audience and Stephen Fry at the bar, as Robert Bathurst paced the length of the room as he delivered his one-man show. It was as funny as expected but it was surprisingly bittersweet too, as Bernard spoke so fondly about the Coach, and of Soho. “Soho’s always waiting with open arms and legs,” said Bernard, who was already writing about the “dying Soho” in his Low Life magazine column in the 1970s. But as Bernard concludes: “Life does go on, whatever proof there might be to the contrary.”

*

A favourite pub is a place where nothing changes – it’s a constant in an uncertain world. So to walk up to a beloved boozer and see the doors closed with that word – “refurbishment” – stapled to the wall, is a kick in the teeth. This is what happened at another one of my favourite Soho boozers, the Blue Posts in Chinatown. Run by Michael Cowell and his partner A Yamashita, it was a pocket of realness in a touristy area. The Blue Posts had a worn-down brown feel and a chill atmosphere, and the place was much loved by locals. When I’d give people the address to meet me there (stressing it’s the one on Rupert Street, not the namesake in Berwick Street), more often than not they’d call me from across the street telling me they couldn’t find it – it was a strangely invisible pub. But one day the doors were shut, and when it opened again, in December 2017, it looked completely different.

Years later, I can see that the new Blue Posts, with its dark-painted wood and brass details, is an objectively beautiful pub. But it took me years to be able to actually go and have a drink there again, spinning on my heels the first time and walking straight back out because it just wasn’t the same. Layo Paskin, the new owner of the Blue Posts, is sympathetic: “There are people who walk in and say, ‘Oh, it’s not like it was.’ But slowly, over a few years, they may start to drift back and have a bit more softness about our approach. I understand it, but change isn’t always bad.”

Paskin, who with his sister Zoë also runs the Palomar restaurant a few doors up, was born in London and spent time in Soho growing up – he was familiar with the Blue Posts before taking it over. He describes its former state as a “dilapidated shell”, and his first port of call was to find out what the 1739-born pub was once like: “We worked with the shape of building to recreate it. We put in Georgian windows and used the flooring that was left to re-do the first floor so it’s all original,” says Paskin.

It takes time to make a local – Paskin says they’ve had the same team working in the Blue Posts since reopening: “It’s miles better now than when we opened, and it will be miles better in another year. You have to build your community – people coming in, feeling it, knowing who runs it. It takes a lot of care and patience.”

The Fallen Heroes, a jazz band who have played the Blue Posts on Sundays for over 12 years, is still part of the scenery, says Paskin, who has a 15-year lease on the Blue Posts and views himself as a custodian: “We’re aware that this pub will be around long after we’ve gone. All we’re here to do is make our period of running the pub really good in its own way. That really is the truth.”

*

There’s a good and a bad way to do a pub refurbishment, and the annual Pub Design Awards from Camra (Campaign for Real Ale) has a category to recognise this. “What we want to see is that people have looked at the building carefully, identified the best features and what’s important about the building, and played to those strengths,” says Andrew Davison, Camra’s Pub Design Awards coordinator. Camra most recently celebrated the Sekforde, a Clerkenwell pub from 1829, and previous refurbishment winners included the Fitzroy Tavern in Fitzrovia, and The Scottish Stores, the former strip pub on Caledonian Road in King’s Cross – all old London pubs restored to original features.

The Camra judges see a lot of exposed brick these days: “An awful lot of refurbishments are very formulaic.” But Davison points out that pubs need to keep evolving – Camra saw more applications in its conversion category this year, as existing buildings (like a slaughterhouse or a pavillion) are converted into pubs. Britain has lost 25 per cent of its pubs in the past 20 years, with one closing every 12 hours. The industry is under extreme pressure, and Davidson says it’s not fair to say you can never change anything.

“People’s idea of what they want from a pub have changed, and a pub is going to evolve to serve its customers,” he says. People nowadays want food and clean toilets, for example, neither of which was standard in pubs back in the day. “What you want is to hang on to the best of the old while allowing things to evolve to meet changing circumstances. If nothing ever changed, I think we’d be losing a lot more pubs.”

*

A good pub is a community. A refurb really needs to be well thought through because unless it’s brilliant, any change will be bad. But Louise Sutherland, a director at pub refurbishment specialist Fairland Contractors, tells me there’s a lot of renovation activity in London these days, across traditional as well as modern pubs. “There’s a lot of small breweries that want to do a really good refurbishment,” she says. “The bigger breweries are also doing a fair bit.”

Fairland has just finished refurb on the Star of the East in Bethnal Green, and the company also worked on the Marquis of Cornwallis in Bethnal Green, The Victoria in Paddington (owned by Fuller’s, who Sutherland describes as a “sympathetic restorer”), and the Crowne Plaza bar in Blackfriars. The current trends are all about outside seating and living walls, wallpapers with strong patterns, ornate features such as monkey lamps, softer seating (getting more women into pubs is a goal), and stuff that looks good on Instagram. Sutherland acknowledges that being too trendy can make spaces look dated: “But pubs get a lot of wear and tear. When your basics are good you can always do an update.”

Sutherland says a simple do-up isn’t rocket science: paint the walls, get rid of the wires, put up some decent pictures and maybe some bric-a-brac, get the lighting right – and don’t rush it. “But the one thing that absolutely makes a great refurb is a good designer. You can tell a mile off if there’s been a designer or if people have done it themselves,” she says. If not, the risk is that it can look tatty: “More often than not, you need someone to come in and help you. You [want] a designer who’s sympathetic to the pub’s history.”

*

The saving grace of the new Blue Posts is that it’s been respectfully renovated with a view to bringing back its original features, a fact that also means it’s sufficiently different to not really remind you of the previous one. This isn’t always the case: when the Nellie Dean on Dean Street reopened after a more or less gentle refurb it had the most ridiculously harsh lighting which made it impossible to be there (for the record, this has since improved). The Market Porter by Borough Market is original dark wood in the front where time stands still, but the back has been refurbished and it’s all clean and bright. While I can understand the need to expand the small space, the dark back corner of the Porter was perfect when I and my fellow night shift workers would roll in at 7am for an after-work drink, looking for a place the sun didn’t reach.

There are still a lot of great little boozers around London where nothing has changed for decades, and for me, all this change is a reminder to visit them while they’re still there. The other Blue Posts (the one on Berwick Street) is still going strong, and so are several other Soho favourites like the French House, the Lyric, and the Cross Keys in Covent Garden.

For pubs that are centuries old, what’s original to you will depend on when you first walked in the door. The old Blue Posts that I loved was probably done up some time around the 1970s, so it’s not like it was “original” – and in fairness, the same is true for the Coach & Horses. I understand that a refurb that to me is a dreaded change, may well become the foundation of someone else’s beloved local in the future. But being a custodian of a London mainstay requires being very, very respectful to what came before.

I still miss the old Blue Posts in Chinatown, but I have to admit that the new external window seats are a brilliant addition. I’m going to be spending some time there this summer, as the alley is a great spot to hang out before going for dim sum – and maybe it’s time to move on. I’m still livid about losing the Coach & Horses, but let’s give Norman Balon the last word – as he said when he retired from the Coach in 2006: “Yesterday is dead. Live for today, and look forward to tomorrow.”